The Joys of Singlehanding

by Gust Stringos, Boston Station, Gulf of Maine Post

Report from the 2019 Bermuda 1-2

FROM JOSHUA SLOCUM TO JEANNE Socrates (SFO) to Jessica Watson, from the first Golden Globe Race to the last Vendee Globe, singlehanded sailing is a long-established tradition among cruising and racing sailors. The Bermuda 1-2, organized by the Newport Yacht Club and the St. George’s Dinghy and Sports Club, is the premier East Coast race for single-handed sailors. It has been sailed biennially since 1977 and combines a singlehanded leg with a double-handed return, with awards for best times in each leg, plus combined time. fellowship among offshore sailors of all nationalities, in the tradition of short-handed sailing and passage making. While recognizing the inherent danger in the sport, the Bermuda 1-2 is organized so as to emphasize, to promote, and to encourage development of techniques, equipment, and technology which will foster safe and seamanlike short-handed sailing.”

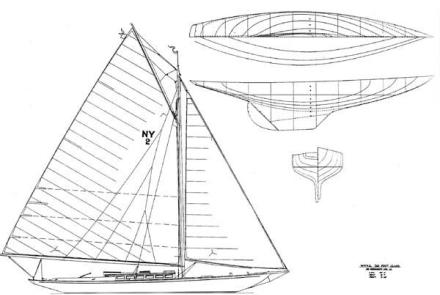

I was happy to be able to join the 2019 race, my sixth. I would once again be sailing on Bluebird, a Morris Justine 36. I find that the anticipation of and preparation for the race helps the long Maine winter pass more quickly. One pays great attention to weather and Gulf Stream patterns. Spring launching is followed quickly with boat-race prep, safety prep, provisioning, and finally, the delivery from Maine to Newport for an early June start.

The race attracted an initial fleet of over 30 boats, ranging from Class 40s to open 6.5 Minis, with racer-cruisers and cruisers of various sizes in between, divided in six classes. After the usual pre-start attrition, the fleet had dropped to 28 boats. The race began with a spinnaker run out of Narragansett Bay in a dying northeast breeze—the last time we would go downwind! Outside of the bay, the wind came from the southeast, making for a tight reach/beat toward the Gulf Stream and Bermuda. At first, conditions were moderate, but the wind gradually picked up into the 20-plus knot range, with building waves causing lots of pounding. This was not at all severe, but uncomfortable and hard on the boats. It certainly contributed to the various damage that caused eight boats to turn around and retire, including autopilot failures, rigging problems, and rudder problems. The race fairly quickly exposes weaknesses in both boats and skippers.

On Bluebird, all remained well except for failure of my Iridium Go!, which eliminated getting weather reports, position updates, and messages from home. However, the race encourages communication between boats, so I wasn’t totally isolated.

After a relatively benign Gulf Stream crossing, the wind shifted to the southwest, giving Bluebird a smooth sail to Bermuda and the finish.

Environmental Notes: While it is difficult to draw conclusions based on a few trips a few years apart, it seemed to me that we were seeing a great increase in the amount of sargassum weed in the vicinity of the Gulf Stream. Sargassum is a floating seaweed that grows in large mats in the Sargasso Sea, the center of the North Atlantic Gyre. Bermuda is at the western edge of the sea, which extends all of the way to the Azores. Most sailboats can go through the mats, but boats with large appendages, such as the Class 40s, find that it can foul their keels and rudders. With warming ocean temperatures, amounts of sargassum have apparently greatly increased, to the point that many beaches in Mexico, the Caribbean, and Florida can become foul and unusable.

On the other hand, the weed mats support lots of life— baby sea turtles hide in them, and American and European eels are born in them, then travel as larvae to U.S. and European rivers and streams, arriving as baby glass eels or elvers. Years later, if they survive fishermen and predators, the mature eels travel thousands of miles back to the Sargasso Sea to spawn and die.

Wildlife: I encountered the usual Gulf Stream suspects: Portuguese Man O’ War jellyfish, sometimes sailing past a becalmed Bluebird. Flying fish flopping on deck. Wilson’s storm petrels crying in the dark. Iridescent Bermuda longtails shimmering on the approach to the finish.

The North Atlantic Gyre is also the home of the “great garbage patch” of floating plastic. Unfortunately, the sargassum mats apparently trap degrading microplastics, with unknown effects to the environment (but I think we can assume that the effects are not good).

On the return leg, just at the continental shelf, we came upon what must have been an upwelling of small fish and nutrients from the depths. Seabirds were diving in a feeding frenzy. Pods of porpoises circled schools of fish. Most exciting of all, countless pairs of finback whales breached all around us, as far as we could see.

“ In today’s world, we don’t get many opportunities to really stretch ourselves. We don’t get time to be by ourselves. We don’t take a break from the mind-numbing pulse of the news. The race provides a healthy antidote to all of that. ”

Double-handed Leg: After a week of rest and recovery on wonderful Bermuda, I was joined by my co-captain, John Priestley, for the return leg. The weather reports were not favorable, with a forecast of strong winds on the nose. Unfortunately, unlike our cruising friends, we cannot put off the start until things look nicer! We started inside the cut at St. George’s and headed out into a 20-knot southwesterly, which eventually shifted to the northwest and picked up to 30 knots. This was combined with a very tight Gulf Stream meander that did not have an obvious good entry and exit point. We were quite seasick the first two days (common for me, but unusual for John!). The wind, waves, and current set us quite far to the east, which would have been very nice if we were headed to Nova Scotia!

The next morning, still a long way from Newport, the wind died and the weather prediction was for continued very light conditions. Other boats calculated their estimated arrival times, found it to be too long, and decided to start their engines and withdraw. Since we didn’t have that option, we continued to claw along on whatever breeze we could find. We eventually did have a great 12 hours in a 15-knot breeze with spinnaker up, bringing us into coastal waters. Finally, in a light breeze, dodging fishing boats, we ghosted across the finish line, sailed up to Newport, and were towed into the harbor, docking just before dark. In this race of attrition, we were the only finishers in Class 4.

The winds eventually moderated, and we recovered and got more or less back on course. We were fairly close to our Class 4 competitors and a few other boats. Then, about 170 nautical miles from Newport, our starter short-circuited and combusted. This put us into energy-saving mode, hand-steering rather than using the autopilot.

Final Thoughts: Being by yourself for five or six days, one experiences many emotional ups and downs, from elation when feeling that you are sailing well, to despair when stuck in an eddy or calm that you think everyone else has avoided. You feel energized when the sun or moon rises out of the sea and apathetic at other times, unrelated to the general fatigue that one feels most of the time. Just moving about the boat, going from handhold to handhold when conditions are rough, requires lots of concentration. Harnesses and tethers become uncomfortable and hamper movement—but they stay on. One gets cold, seasick, and very tired. You and the boat get very beat up. So why keep doing this?

Before and during the race, one has to work on physical, but especially mental, preparation—patience, stamina, and pacing. Especially on the solo leg, it’s an exercise in mindfulness.

In today’s world, we don’t get many opportunities to really stretch ourselves. We don’t get time to be by ourselves. We don’t take a break from the mind-numbing pulse of the news. The race provides a healthy antidote to all of that.

Finally, while the sailors are all very competitive, we know that we are all there for each other, ready to help, and that this bond is much more important than winning. Sometimes, the help takes the form of a heroic rescue; more often, it is simply standing by, giving emotional support over the VHF. A tremendous feeling of camaraderie and bonding develops. I haven’t experienced this in too many other situations. I look forward to the next race! 2

*For more information on the Bermuda 1-2, see bermuda1-2.org*

ABOUT THE AUTHOR Gust Stringos lives in Central Maine, where he has worked for more than 30 years as a family-practice physician. He and his wife, Jan, sail their Morris Justine 36, Bluebird, out of Rockland, Maine, exploring the coast from Cape Cod to Nova Scotia to Bermuda, but mostly enjoying their home waters of Penobscot Bay. In 2005-06, they sailed around the Atlantic via the Azores, Madeira, Canary Islands, Caribbean, and the Bahamas. They are pictured here in St. George’s, Bermuda. Gust is looking forward to his 13th Bermuda race in June 2020.